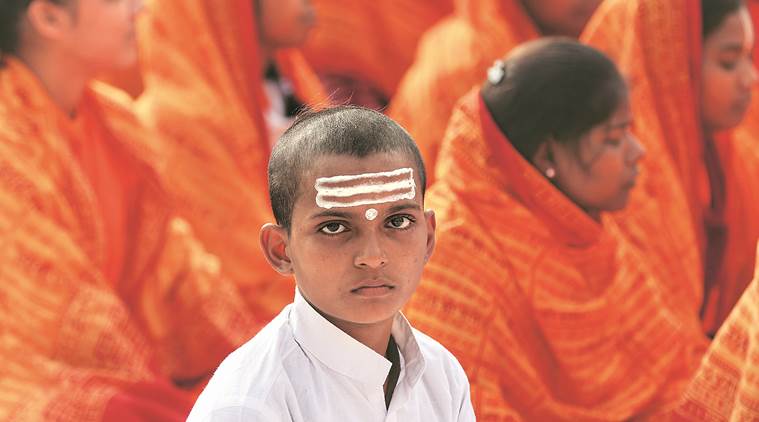

At a Hindu gathering in Ayodhya Wednesday. (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)Kolkata is where I was born and lived till the age of 17, when I left for college in Delhi. It is a city I visit regularly and where I maintain a home. Maybe because of this familiarity, I never felt the need to write about it.

At a Hindu gathering in Ayodhya Wednesday. (Express Photo by Vishal Srivastav)Kolkata is where I was born and lived till the age of 17, when I left for college in Delhi. It is a city I visit regularly and where I maintain a home. Maybe because of this familiarity, I never felt the need to write about it.

That changed earlier this month, when on a whim I decided to spend a night in Belur Math, the Ramakrishna Mission (RKM) temple-complex on the western banks of the Ganga, on the edge of the city. Here is the mission’s own description of Belur: “Sprawling over forty acres of land on the western bank of the Hooghly (Ganga)… a place of pilgrimage for people from all over the world professing different religious faiths. Even people not interested in religion come here for the peace it exudes.” That last sentence meant I would not be unwelcome.

You arrive there ploughing through Kolkata’s winding alleyways and over-crowded streets, with lonely men in shirt-sleeves leaning out of windows, and then suddenly it appears, a place of strange serenity, basking on the bank of the old river, Ganga, exuding the same sense of timelessness, captured in so many songs, from Bhupen Hazarika’s tribute to the Brahmaputra to the Pussycats’ “Mississippi”.

Swami Vivekananda’s own lines penned some 120 years ago, in his little room overlooking the river, captures this well: “Here I am writing in my room on the Ganga, in the Math. It is so quiet and still! The broad river is dancing in the bright sunshine, only now and then an occasional cargo boat breaking the silence with the splashing of the oars.”

What is remarkable about RKM is its organisational excellence. You see this in the schools, colleges and hospitals it runs all over India. Despite the thousands of visitors and tourists dropping in every day at Belur, the premises are spotless. Its various activities — from a variety of social work to the chanting of hymns — run with clockwork precision.

I got a sense of that when my wife and I arrived at the Mission’s International Guest House early in the evening of June 12 and the check-in clerk cheerfully told us that breakfast would be served at 6.30 am. I asked him the standard question in hotels: Up to what time would breakfast be served? He looked nonplussed. “It is at 6.30,” he repeated with an emphasis on the “at,” which said it all.

There was nothing much to do in the evening. We chatted with several of the monks and some of the visitors, and listened to the mystical chanting by the missionaries, set to the strains of dhrupad, in the cavernous main temple, with people sitting in complete silence. By the time we stepped out, it was late, late in the evening, the crowds they were gone; the clocks had ceased their chiming, and the deep river ran on.

The International Guest House is just outside the formal premises of the mission. It is on the bend of a narrow lane next to a pir dargah where we could see a couple of men conversing late into the night. Clearly, the whole area is under some supervision by the Ramakrishna Mission because the lane is quiet and clean with a few bright overhead lights, which defy the darkness of the night. Between the slats of our shuttered window one can see the occasional passerby — monks in saffron and white, stray workers returning home from the day’s toil, and women in traditional white saris with red borders and bindis adorning their foreheads.

The challenge was the next morning. The mangalarati, we are told, is not to be missed. It takes place at 4 am, sharp, needless to add. The walk down the deserted alley in the darkness of the night, with those quiet overhead street lights, and homes on both sides with shuttered windows could have been a scene in an Eliot poem or a bylane in Cavafy’s Alexandria. The mangalarati and the breaking of dawn over the river had a spiritual quality that made my imagination drift back to India’s Vedic times. It must have been this blending of everyday life with the mysteries of nature that sparked the deep philosophical musings that make the Vedas so special.

I cannot thank the Ramakrishna Mission enough for the warm and cordial welcome it gave us. I needed it not just because in the rough and tumble of everyday life, we spend so little time to meditate about life’s unknowns, where we come from, why and where we are headed, but also because I needed to see this face of Hinduism — philosophical, tolerant, and embracing of other religions.

This is so different from what is being propagated in the name of Hinduism by today’s right-wing Hindutva groups. Chatting with the young monks, and the visitors to the temple, I also felt good to see most of them clamouring to separate themselves from the narrow-minded Hinduism and the hatred of Islam, Christianity and Judaism being preached by some groups, and the murders and hate being spewed out in the name of protecting the cow. It was good to see ordinary Hindus realising that they do not want to be part of this culture of hate.

One reason why Vivekananda set up the Mission here was that it is close to Dakshineshwar, a temple built by Rani Rashmoni, who, being low-caste, had difficulty finding a Brahmin priest. She eventually found two renegade brothers. The younger one, Ramakrishna, especially broke all the rules and rituals of religion with alacrity and had a simple message of universal love, which was echoed by his disciple, Swami Vivekananda, in his famous Chicago address, on September 11, 1893: “I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honour of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism.”

And for us it is well worth remembering what the current president of RKM, quoting Vivekananda’s speech, wrote, “A century has gone by since these words were uttered. At the fag end of this 20th century, one feels that we are travelling backwards towards the age of barbarism, when might was right and group loyalties alone counted.”

For all the latest Opinion News, download Indian Express App